Who decided the ‘Seven Wonders of the Ancient World’? There was no global council, no universal vote and no official authority deciding what counted as a ‘wonder’. What we know today as the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is the result of Greek observation, documentation and cultural continuity – a list shaped by travel, literacy, survival of texts and a particular idea of greatness. Understanding how this list came into being reveals not only the story of ancient monuments, but also leads us to the real ‘wonder’ in human lives.

- What Did ‘Wonder’ Mean in the Ancient World?

- Who Documented the Seven Wonders?

- The List Reflected the Greek Travel World

- No Competing Written Lists Survived

- Later Generations Mistook Tradition for Authority

- Who Decided Which Monuments Became the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World?

- Herodotus (5th century BCE)

- Callimachus of Cyrene (3rd century BCE)

- Greek Epigrammatist Antipater of Sidon (2nd Century BCE)

- Why Did the Greek List of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Become ‘Global’?

- The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: Why Only These Seven Were Chosen

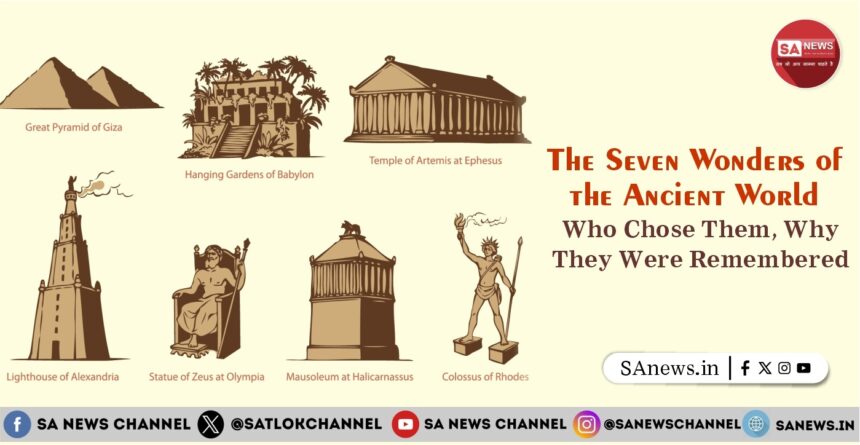

- The Great Pyramid of Giza (Egypt)

- The Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Mesopotamia)

- The Statue of Zeus at Olympia (Greece)

- The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (Turkey)

- The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (Turkey)

- The Colossus of Rhodes (Greece)

- The Lighthouse of Alexandria (Egypt)

- A Common Thread Among the Seven Wonders

- Humanity Built Wonders But Forgot Why It Was Born

- FAQs: The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

What Did ‘Wonder’ Mean in the Ancient World?

The seven wonders of the ancient world were actually derived from Greek memory. Several Greek travellers who set out to explore the world documented their travels, everything they saw. Repeated mention of certain places resulted in the world adopting select seven places as the wonders of the ancient world. But how does one define wonder?

The ancient Greeks did not use the modern phrase ‘wonders of the world’. Instead, they spoke of ‘theamata’ which literally means ‘things worth seeing’ in Greek language.

A ‘wonder’ was not defined by moral value, human compassion or ethical impact. It was defined by awe.

For Greek travellers and scholars, a structure deserved remembrance if it:

- Was created by human effort, not nature

- Displayed extraordinary scale or technical mastery

- Represented the height of a civilisation

- Challenged the limits of what humans believed possible

- Could be visited or known within the Greek world

In essence, the question was never ‘Is this good?’

It was ‘How could humans have done this?’

Who Documented the Seven Wonders?

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World are better understood as ‘The Seven Wonders of the Ancient Greek Worldview’. They reflect Greek curiosity, travel and aesthetics, not a global judgement.

After Alexander the Great, Greek language and ideas spread across Egypt, Persia and parts of Asia. Therefore, when later civilisations wanted to understand the ancient past, the only study material available were Greek travelogs, maps, notes, etc. So the Greek worldview became the lens through which history was taught, especially in Europe, and eventually globally.

The Greek shaped the written record of the ancient world.

The List Reflected the Greek Travel World

The Seven Wonders were not ‘global’ wonders, instead, they were:

- Wonders Greeks could travel to

- Located around the Mediterranean and Near East

- Mostly within or near Greek-influenced regions

- Great monuments in India, China, Africa (beyond Egypt) and the Americas were simply outside Greek awareness.

So the list was geographically limited and not universally representative.

No Competing Written Lists Survived

Other civilisations built extraordinary monuments, such as:

- The Great Wall of China

- Indian rock-cut temples

- Mesopotamian ziggurats beyond Babylon

- African and Mesoamerican pyramids

But no equally popular, well-preserved and widely transmitted lists from those cultures reached later generations in the same way as Greek travel literature.

Later Generations Mistook Tradition for Authority

As discussed earlier, over time the Greek list was repeated in Roman writings, medieval manuscripts and European education systems

Eventually, it became ‘the’ list, not because it was officially chosen, but because it was inherited.

Who Decided Which Monuments Became the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World?

Contrary to popular belief, no single Greek individual selected the Seven Wonders. The list evolved gradually between the 5th and 2nd centuries BCE, shaped by a small circle of Greek travellers, poets and scholars.

Key figures include:

Herodotus (5th century BCE)

Often called the ‘Father of History’, Herodotus travelled extensively through Egypt, Persia and Babylon. He described the Pyramids and other monumental structures with fascination. While he never created a formal list, his writings laid the groundwork for later classifications of extraordinary sights.

Callimachus of Cyrene (3rd century BCE)

A scholar at the Library of Alexandria, Callimachus was known for organising knowledge into catalogues and lists. Although his specific work on wonders has not survived, he is believed to have helped formalise the idea of recording remarkable man-made structures.

Greek Epigrammatist Antipater of Sidon (2nd Century BCE)

Antipater is the most decisive figure in the history of the Seven Wonders. In a short but influential poem, he explicitly named most of the seven specific monuments together. He wrote:

This is the earliest surviving source that clearly presents the canonical list as we know it today.

Later writers such as Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Pliny the Elder repeated the similar monuments, reinforcing the list through tradition and repetition.

By approximately 150‐100 BCE, the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were effectively fixed.

Why Did the Greek List of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World Become ‘Global’?

The Greeks did not possess worldwide political authority. However, they held something equally powerful – written records that survived uninterrupted.

Greek texts strongly influenced Roman education. As mentioned earlier, they were also preserved by medieval scholars of the western world. In fact, Greek texts were revived during the Renaissance, thereby, becoming foundational to modern Western education.

However, several extraordinary structures never made it to this list because the majority of the travellers who documented their travels were Greek. Other civilisations, such as those in India, China, Africa and the Americas, built extraordinary monuments of equal or greater significance. However, their literature did not pass through the same continuous chain of preservation, translation and teaching.

As a result, what survived Greek literature became global history, while many other achievements faded from collective memory.

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: Why Only These Seven Were Chosen

Each of the Seven Wonders represented a distinct peak of human achievement, as perceived by the ancient Greek worldview.

Let us now examine each of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The Great Pyramid of Giza (Egypt)

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the tallest among the colossal royal tombs of ancient Egypt. Constructed with extraordinary precision, the Great Pyramid consists of an estimated 2.3 million stone blocks. Its alignment with cardinal directions remains one of the most remarkable achievements of ancient engineering.

Key facts:

- Location: Giza Plateau, Egypt

- Built: circa 2560 BCE

- Commissioned by: Pharaoh Khufu

- Height: Originally about 146 metres

- Materials: Limestone and granite

- Status: Only surviving ancient wonder

The Great Pyramid of Giza (recent image)

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

Already ancient when the Greeks encountered it, the Great Pyramid astonished them with its immense scale, precision and longevity. Built without iron tools or modern machinery, it symbolised human organisation, mathematics, and endurance on an almost unimaginable level.

To reiterate, it remains the only surviving wonder.

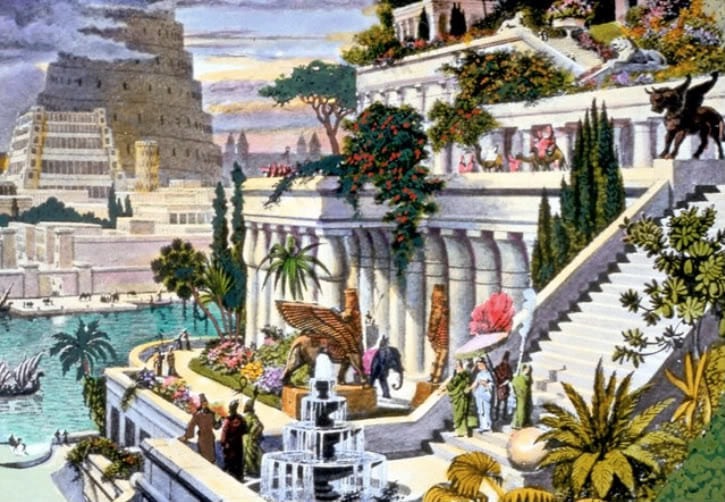

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon (Mesopotamia)

They were a series of elevated stone terraces overflowing with trees, flowering plants and cascading greenery, engineered to rise above the flat plains of Mesopotamia.

According to tradition, this extraordinary garden was said to have been built atop a man-made terrace to delight King Nebuchadnezzar II’s queen, although many historians continue to question whether it ever truly existed. Ancient descriptions suggest an innovative irrigation mechanism capable of raising water from the Euphrates River – an engineering feat far ahead of its time.

Key facts:

- Location: Traditionally Babylon (modern-day Iraq)

- Built: Possibly 6th century BCE

- Attributed to: King Nebuchadnezzar II

- Structure: Terraced stone platforms

- Irrigation: Advanced water-lifting systems

- Status: Existence debated

Excavation site image of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Given below is an artwork of how the original Hanging Gardens of Babylon could have been. Produced in the 19th century after the first archaeological discoveries in the Assyrian capitals, this hand-coloured engraving presents an artistic vision of the mythical Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of antiquity’s most celebrated wonders:

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

Described as a terraced garden rising in a desert city, the Hanging Gardens represented the idea of nature being lifted and sustained by human engineering. Whether entirely real or partially legendary, the concept itself captured Greek imagination.

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia (Greece)

A towering seated figure of the god Zeus, crafted from gold and ivory, filling the interior of his temple and projecting both majesty and divine authority. The statue dominated the Temple of Zeus, portraying him seated in majesty, reinforcing Olympia’s religious significance during the Olympic Games.

Key facts:

- Location: Olympia, Greece

- Built: c. 435 BCE

- Sculptor: Phidias

- Height: about 12 metres

- Materials: Gold and ivory (chryselephantine)

- Fate: Destroyed or lost by late antiquity

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia (representation as a sculptured art-form)

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

Crafted from gold and ivory by the sculptor Phidias, the statue was believed to embody the presence of Zeus himself. It demonstrated how art could transcend material form and evoke the divine.

Also Read: Creation Story of the Internet | Genesis and Full History

The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (Turkey)

An immense marble temple surrounded by rows of tall, finely carved columns, designed to honour the goddess Artemis and dominate the landscape of the ancient city. Its immense size and artistic detailing made it one of the most impressive religious structures of the ancient Mediterranean.

Key facts:

- Location: Ephesus (modern-day Turkey)

- Built: 6th century BCE (rebuilt multiple times)

- Style: Ionic

- Columns: More than 120 marble columns

- Patronage: Supported by regional rulers

- Fate: Destroyed by invasion and neglect

Image of the ruins of the Temple of Artemis

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

Built entirely of marble and far larger than most Greek temples, it represented architectural harmony, devotion and perfection. Its repeated reconstruction after destruction added to its legendary status.

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (Turkey)

A monumental stone tomb combining a stepped base, towering columns and a pyramidal roof, richly decorated with sculptures and reliefs, built for King Mausolus. The Mausoleum’s fusion of architectural styles influenced monumental tomb construction for centuries to come.

Key facts:

- Location: Halicarnassus (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey)

- Built: c. 350 BCE

- Commissioned by: Artemisia II

- Height: approximately 45 metres

- Materials: Marble

- Fate: Gradual destruction by earthquakes

A model of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus made in plastic and house at the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archeology

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

This monumental tomb blended Greek, Persian and Egyptian styles. Its influence was so profound that the word ‘mausoleum’ originates from it. To the Greek, it symbolised memory, legacy and the human desire to defeat oblivion.

The Colossus of Rhodes (Greece)

A gigantic bronze statue of the sun god Helios, standing upright near the harbour of Rhodes and towering over ships entering the port. Despite standing for only a few decades, the Colossus left an enduring legacy as a symbol of civic pride and artistic daring.

Key facts:

- Location: Rhodes, Greece

- Built: c. 280 BCE

- Sculptor: Chares of Lindos

- Height: approximately 33 metres

- Material: Bronze

- Fate: Collapsed during an earthquake (226 BCE)

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

A towering bronze statue built from war spoils, the Colossus stood briefly but left a lasting impression. It embodied human ambition and boldness, daring to rival the gods in scale.

The Lighthouse of Alexandria (Egypt)

A massive multi-tiered stone tower rising from the shoreline, crowned with a blazing beacon that guided sailors safely towards the harbour of Alexandria. By building the world’s first lighthouse, the Pharos combined architecture, science and public service, setting the standard for lighthouse design for centuries.

Key facts:

- Location: Island of Pharos, Alexandria, Egypt

- Built: c. 280 BCE

- Height: 100-130 metres (est.)

- Function: Navigation aid

- Technology: Fire and reflective surfaces

- Fate: Destroyed by earthquakes

A drawing of the Lighthouse of Alexandria done by Professor H. Thiersch

Why it mattered to the Greeks:

One of the tallest structures of the ancient world, the lighthouse used fire and reflective surfaces to guide ships safely to harbour. Located near the Library of Alexandria, it symbolised knowledge applied for human benefit.

A Common Thread Among the Seven Wonders

Aside from the fact that the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were well documented in Greek travel literature, it is important to note that each wonder represented a different civilisational ideal, such as:

- Organised power

- Engineering mastery

- Artistic excellence

- Architectural perfection

- Legacy and remembrance

- Ambition and confidence

- Knowledge in service of society

They were not chosen for compassion or ethical impact, but for their ability to inspire awe and disbelief.

Humanity Built Wonders But Forgot Why It Was Born

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were monuments that inspired awe among ancient Greek travellers. Through their writings and narratives, that sense of wonder was passed down across centuries. Today, we admire these structures largely through Greek descriptions, especially since most of them lie in ruins or no longer exist at all.

This raises an important question: Are towering structures and extraordinary engineering feats truly the greatest wonders of humanity?

Human beings spent decades, even generations, shaping stone into legacies meant to defy time. And while many succeeded in carving their names into history, these achievements ultimately remain lifeless monuments – silent, unmoving and impermanent.

In contrast, the greatest wonders of the world are not stone structures, but those human lives spent without the refuge of a Tatvdarshi Sant (Complete Saint).

Jagatguru Tatvdarshi Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj discloses that the true purpose of this rare human birth is not to chase merely worldly recognition, but complete salvation which is attainable only under the refuge of a Tatvdarshi Sant (Complete Saint). Without this spiritual guidance, even the most accomplished human life remains incomplete.

Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj cites the divine speech of Supreme God Kabir, revealing the profound truth about human existence and its ultimate goal:

Here lies the deepest irony of human history.

Humanity succeeded in breathing legacy into stone, elevating lifeless structures to the status of ‘wonders of the world’. But, by neglecting the true aim of life, many humans fail to do complete justice to their precious human life.

Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj poignantly explains that a human life, when lived without true spiritual knowledge, becomes no different from stone itself – unaware, unfulfilled and bound by illusion. This comparison powerfully underscores the immense value of human birth and the tragedy of allowing it to go to waste.

To understand the real purpose of human life, and to walk the path that leads to complete liberation, one must seek refuge under the guidance of the sole Tatvdarshi Sant present in the world today – Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj.

For those who sincerely wish to explore this truth, listen to the deeply transformative spiritual discourses of Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj and begin the journey towards true salvation. Visit:

FAQs: The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Q1) What are the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World?

Answer: The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World are iconic monuments admired by ancient Greeks for their extraordinary scale, craftsmanship, and engineering brilliance.

Q2) Who selected the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World?

Answer: The list evolved through writings of ancient Greek travellers and scholars, rather than being chosen by any single authority or official body.

Q3) Why is only one of the Seven Wonders still standing today?

Answer: Most were destroyed by natural disasters, wars, or neglect over centuries, while the Great Pyramid of Giza survived due to its massive and durable construction.