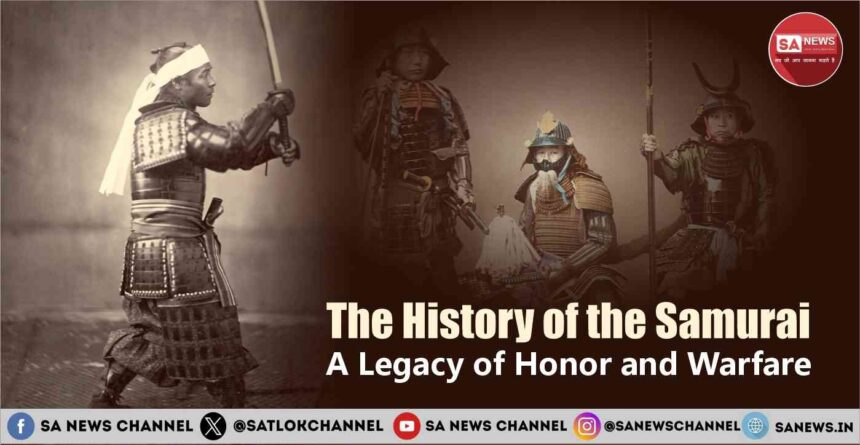

The origins of the samurai class can be traced back to the Heian Period (794–1185) in Japan. The word “samurai” (侍) comes from the Japanese verb “saburau”, meaning “to serve” or “to accompany a person of high rank.” Originally, the term referred to those who served the nobility as guards or retainers. As the imperial court’s control over distant provinces weakened, powerful clans began to employ these armed retainers to manage regional conflicts and protect their interests. Over time, these warriors formed a distinct social class, marked by martial skill, loyalty, and a strict ethical code. Their transformation from provincial guards to elite warriors laid the foundation for Japan’s feudal structure.

- Rise of the Samurai Class during the Kamakura Shogunate

- The Samurai and the Bushido Code

- Mongol Invasions and Samurai Resilience

- Ashikaga Shogunate and the Warring States Period

- The Unification of Japan under Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa

- Life of the Samurai in the Edo Period

- The Decline of the Samurai

- Saigo Takamori and the Satsuma Rebellion

- Cultural Legacy of the Samurai

- Samurai Influence on Martial Arts and Literature

- Western Perceptions and Popular Representations

- A Historical Force and Cultural Icon

- Samurai and Spirituality: The Hidden Faith Behind the Sword

- FAQs related to the History of the Samurai

Rise of the Samurai Class during the Kamakura Shogunate

The Genpei War (1180–1185), fought between the Minamoto and Taira clans, marked a pivotal turning point in the history of the samurai. The victory of the Minamoto clan and the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1192 under Minamoto no Yoritomo institutionalized the samurai’s role in governance. This period introduced the bakufu (military government) system, where the shogun wielded real power while the emperor remained a symbolic figure.

Samurai were now not only warriors but also administrators and enforcers of the law in the provinces. Their influence deepened as land ownership and military service became intertwined, consolidating the samurai’s place in Japanese society.

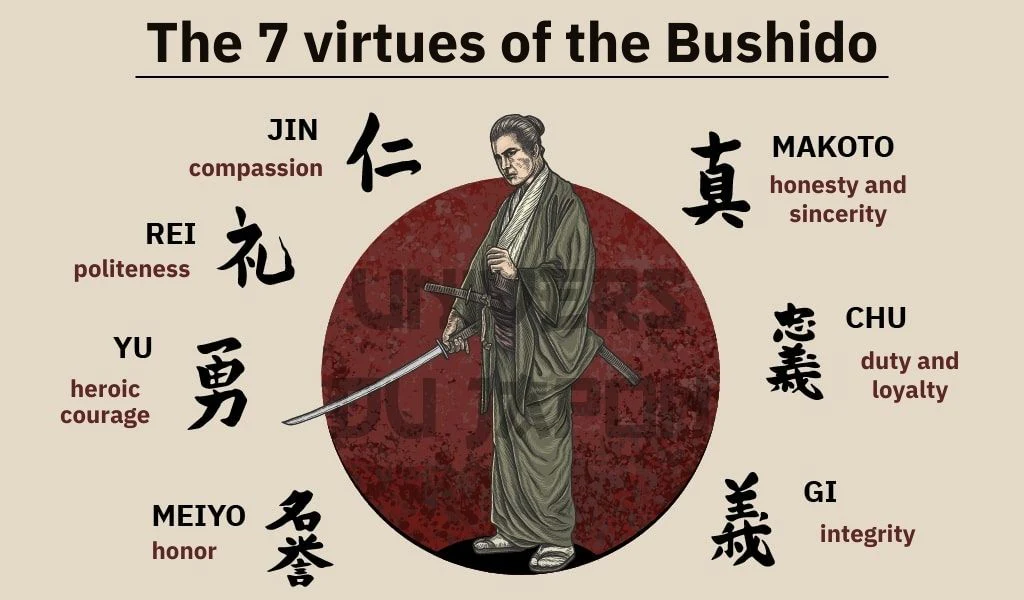

The Samurai and the Bushido Code

By the 13th century, the samurai ethos had begun to formalize into what would later be recognized as bushido, or “the way of the warrior.” This moral code emphasized loyalty, honor, courage, and self-discipline. Bushido was not codified during its early formation but was reflected in the conduct expected of samurai in both war and governance.

Death was often preferable to dishonor, and ritual suicide (seppuku) became a means to restore one’s honor in the face of failure or disgrace. Although interpretations of bushido varied across time and clans, it remained a central tenet of samurai life and continues to influence Japanese culture today.

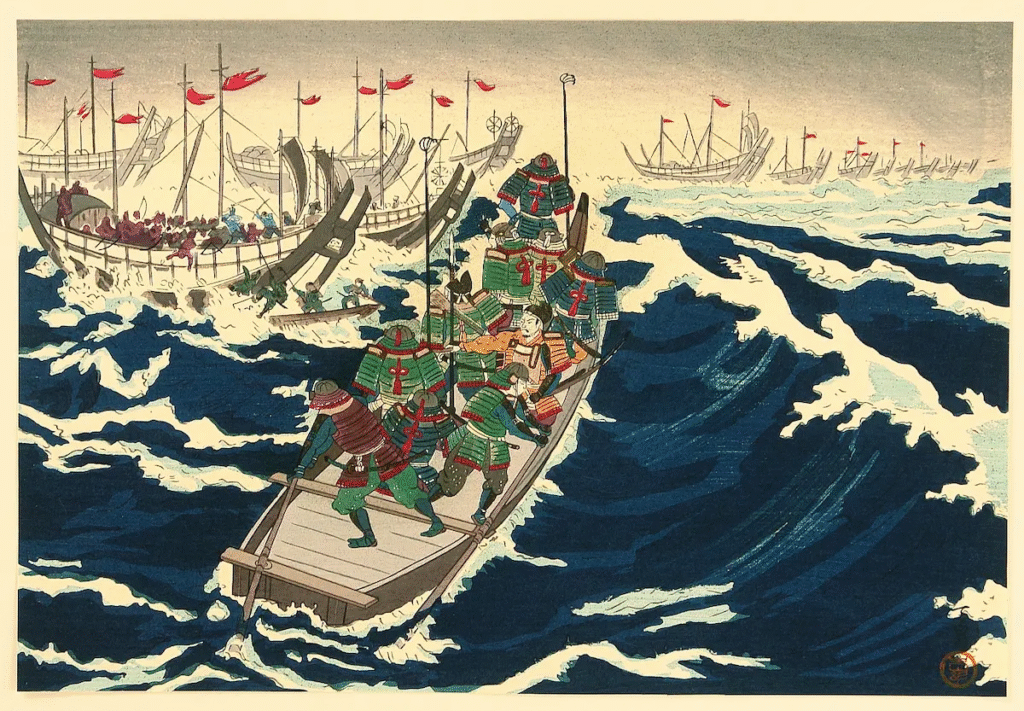

Mongol Invasions and Samurai Resilience

The Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 under Kublai Khan tested the military capabilities of the samurai class. Although the Mongols brought advanced tactics and overwhelming numbers, the samurai resisted fiercely, engaging in guerrilla-style warfare that contrasted with the Mongols’ structured military strategies.

The second invasion was famously thwarted by a typhoon, later romanticized as the “kamikaze” or divine wind. These invasions highlighted the importance of fortifications, cooperative military action, and maritime defense. The conflicts also exposed the limitations of the shogunate’s reward system, as many samurai were left uncompensated, sowing seeds of discontent that would affect later periods.

Ashikaga Shogunate and the Warring States Period

The fall of the Kamakura Shogunate in 1333 and the rise of the Ashikaga Shogunate ushered in a more tumultuous era. While the Ashikaga family managed to centralize power initially, internal strife and weak leadership eventually led to the Ōnin War (1467–1477), plunging Japan into a century-long conflict known as the Sengoku or Warring States period.

During this time, samurai lords (daimyo) competed for territorial dominance, and traditional loyalties were frequently undermined by shifting alliances. The samurai adapted by becoming not just warriors but also political strategists, castle builders, and administrators. This era saw innovations in military tactics and the introduction of firearms, which gradually altered samurai warfare.

The Unification of Japan under Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa

The late 16th century marked a major shift in samurai history with the unification of Japan under three powerful leaders, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Nobunaga was instrumental in modernizing Japan’s military through the extensive use of arquebuses (early firearms), while Toyotomi Hideyoshi completed the unification efforts. Hideyoshi implemented policies that froze the social structure, forbidding peasants from bearing arms and thus solidifying the samurai as a hereditary warrior class.

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 led to the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which would rule for over 250 years. Under Tokugawa rule, the samurai transitioned from battlefield warriors to bureaucrats and scholars, maintaining their status through intellectual and administrative contributions.

Life of the Samurai in the Edo Period

The Edo Period (1603–1868) brought about lasting peace and stability under the Tokugawa Shogunate. This peace, while beneficial for the country, diminished the samurai’s traditional role as warriors. Many became administrators, teachers, or retainers to daimyo in castle towns. The rigid class system instituted during this era placed samurai above peasants, artisans, and merchants, but economic realities often contradicted this hierarchy.

Also Read: Unfolding the History of the American West: From Native Lands to Modern Frontiers

Samurai were paid in rice stipends rather than money, and inflation along with economic changes left many impoverished. Despite this, they continued to adhere to bushido ideals, and the period saw a flourishing of samurai literature, martial arts, and Neo-Confucian philosophy.

The Decline of the Samurai

The arrival of Western powers in the mid-19th century posed new challenges to Japan’s isolationist policies. The Treaty of Kanagawa in 1854, signed under American pressure, marked the end of sakoku (national seclusion). This foreign intervention exposed the technological and military inferiority of Japan compared to Western nations. The need for modernization led to internal conflicts, including the Boshin War (1868–1869), which pitted samurai loyalists of the shogunate against forces supporting imperial restoration.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 dismantled the feudal system and abolished the samurai class. Samurai stipends were commuted into government bonds, the wearing of swords was prohibited, and a conscripted national army replaced the hereditary warrior class.

Saigo Takamori and the Satsuma Rebellion

One of the most iconic episodes in the final chapter of samurai history was the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, led by Saigo Takamori, a former samurai and government official. Disillusioned by rapid Westernization and the perceived erosion of traditional Japanese values, Saigo and thousands of former samurai rebelled against the Meiji government.

Although the rebellion was ultimately crushed by the imperial army, it represented the last significant resistance by the samurai class. Saigo’s death symbolized the end of the samurai era, but he remained a revered figure, often romanticized as a tragic hero who embodied the spirit of bushido even in the face of inevitable change.

Cultural Legacy of the Samurai

Though the samurai as a social class ceased to exist, their cultural and philosophical legacy endured. Bushido ideals continued to influence Japanese ethics, education, and national identity. The samurai became symbolic of loyalty, discipline, and sacrifice, qualities emphasized in both literature and modern institutions such as the Japanese military and corporate culture. Their image was further popularized through kabuki theater, woodblock prints, and later, film and literature.

During Japan’s militarist expansion in the early 20th century, samurai values were invoked to foster nationalism, though often in distorted forms. Today, the samurai represent a complex blend of historical reality and cultural mythology that remains deeply embedded in Japanese consciousness.

Samurai Influence on Martial Arts and Literature

Traditional samurai training encompassed a wide range of martial disciplines, including kenjutsu (swordsmanship), kyudo (archery), and jujutsu (unarmed combat), many of which evolved into modern martial arts like kendo, judo, and aikido. These disciplines emphasize not just technique but also mental focus and spiritual development, reflecting the holistic approach of samurai training.

In literature, samurai figures have been depicted in historical chronicles, philosophical texts, and modern novels. Works such as The Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi and Hagakure by Yamamoto Tsunetomo continue to be studied for their insights into strategy, discipline, and ethics. The samurai’s contribution to Japanese literature and martial arts remains a testament to their enduring cultural relevance.

Western Perceptions and Popular Representations

In the 20th century, the samurai captivated global audiences through films, novels, and academic studies. Directors like Akira Kurosawa introduced the samurai ethos to the world in films such as Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, which inspired Western adaptations like The Magnificent Seven. The samurai archetype also influenced Western storytelling, contributing to the creation of the modern action hero and shaping characters in Hollywood, comics, and video games.

While these portrayals often romanticize samurai life, they also reflect universal themes of honor, loyalty, and resilience. The fascination with samurai culture abroad underscores its powerful symbolic resonance beyond Japan.

A Historical Force and Cultural Icon

The samurai were more than just warriors; they were pivotal actors in Japan’s political, social, and cultural evolution. From their rise during the Heian period to their transformation under the Tokugawa regime and eventual dissolution during the Meiji Restoration, the samurai left an indelible imprint on Japanese history.

Their disciplined lifestyle, philosophical depth, and martial prowess continue to inspire admiration and reflection. Though they no longer exist as a social class, the samurai remain timeless symbols of honor, courage, and devotion to duty, a legacy that transcends centuries and borders.

Samurai and Spirituality: The Hidden Faith Behind the Sword

The samurai, the elite warrior class of feudal Japan, followed a spiritual and ethical code deeply rooted in a blend of religious traditions. Their way of life, known as Bushidō (the “Way of the Warrior”), was influenced primarily by Shinto, Zen Buddhism, and Confucianism. Shinto, the indigenous faith of Japan, encouraged reverence for kami (spiritual deities), nature, and ancestral spirits. Samurai prayed to these forces for protection and strength, regularly participating in rituals at Shinto shrines and honoring their clan’s lineage.

Zen Buddhism played a critical role in shaping their mindset, its teachings of discipline, mindfulness, and detachment from fear helped samurai achieve mental clarity and calm before battle. Practices like zazen (seated meditation) and acceptance of mu (nothingness) were common. Confucianism, introduced from China, provided a moral and ethical framework that emphasized loyalty, righteousness, and respect for social hierarchy.

This fusion of beliefs led the samurai to view loyalty to their daimyō (feudal lord) as sacred, often valuing duty above their own life. They also expressed their spiritual beliefs through symbolic acts, such as writing death poems (jisei no ku) before going to battle, a practice that reflected calm acceptance of death. Despite their devotion to these traditions, their worship did not offer eternal liberation.

Hence, According to Chyren Saint Rampal Ji Maharaj, true salvation is only attainable through devotion to the Supreme God Kabir, as described in the Bhagavad Gita Chapter 15 Verses 1–4. Human life is uniquely precious among 84 lakh life forms, meant not for warfare or dying in honor, but for seeking the path of true worship that leads to Satlok, the eternal realm. The samurai code inspired honor and discipline, but only the teachings of a Tatvdarshi Saint can guide one to complete spiritual freedom.

As Sant Rampal Ji Maharaj rightly says:

“Do not follow spiritual customs blindly. Measure them against holy scriptures. Only then will you find the true path that leads to eternal peace.”

We invite all seekers, especially in Japan, to reflect deeply, examine their scriptures, and begin the spiritual path. Visit www.jagatgururampalji.org or read Gyan Ganga to start your journey toward eternal peace and liberation.

FAQs related to the History of the Samurai

1. Who were the samurai in Japanese history?

The samurai were a warrior class in feudal Japan known for their military skill, discipline, and adherence to a strict ethical code called bushido. They served feudal lords (daimyo) and played key roles in governance, warfare, and administration from the 10th century until their decline in the late 19th century.

2. What is bushido and how did it influence the samurai?

Bushido, meaning “the way of the warrior,” was the code of conduct followed by samurai. It emphasized virtues such as loyalty, honor, courage, and self-sacrifice. Bushido shaped the samurai’s actions both on and off the battlefield and left a lasting impact on Japanese moral and cultural values.

3. When and why did the samurai era end?

The samurai era ended during the Meiji Restoration in 1868. The modernization and centralization of Japan’s military, economy, and governance made the samurai class obsolete. The new national army replaced their role, and laws were introduced to abolish their privileges, such as the right to bear swords.

4. How did the samurai influence modern Japanese society?

Samurai values like discipline, loyalty, and perseverance continue to influence Japanese society, particularly in education, corporate culture, and martial arts. Their stories and ideals are preserved in literature, film, and national identity, symbolizing honor and ethical strength.

5. Were all samurai skilled swordsmen?

While swordsmanship (kenjutsu) was a core part of samurai training, not all samurai were expert swordsmen. Many also specialized in archery, horseback riding, and later, firearms. In the Edo period, many samurai served as bureaucrats and scholars, balancing martial skills with administrative duties.